Antoni Gaudí and Contemporary Architecture

The Modernist Genius Transcends Time and Continues to Inspire Today’s Architects

Casa Vicens restoration with sculptural staircase by Martínez Lapeña – Torres Arquitectos, © Pol Viladoms/Casa Vicens

An Approach to the Timeless Figure of Gaudí

Antoni Gaudí’s architecture has fascinated generations of architects and amateurs who have always tried to interpret it, often approaching it as if it were a jumble of enigmas. The symbolic complexity of his work is evident, which has encouraged such approaches. But Gaudí’s work is much more than forms and symbols, and here we will first try to give some basic guidelines that will help to have a global and contextualized vision of his legacy, but above all to understand the validity of his ideas and his work, which were ahead of their time, but which also continue to inspire architects and artists in the creation of contemporary works.

Gaudí and Modernisme

The first step is to understand the social and cultural context in which Gaudí’s work arises. Barcelona underwent a drastic transformation in the last decades of the 19th century, thanks in large part to the industrial revolution, which resulted in an economic boom, a cultural renaissance, but also in social conflicts.

In this context, Modernista architecture appeared as an expression of a new industrial bourgeoisie. A complex, fascinating and even contradictory movement that developed in parallel with international Art Nouveau and absorbed diverse theoretical and stylistic influences, among which Gothic and Moorish architecture (including Islamic and Mudejar references) stand out. From this accumulation of components, a unique architecture emerges, which despite its eclectic tendency, can reach a surprising level of harmony. Moreover, it tries to project itself into the future, incorporating industrial materials and techniques without renouncing exuberant ornamentation. Although Gaudí’s work will be unique in many ways, it is from this perspective essentially Modernista.

Rooftop terrace of Casa Milà featuring sculptural chimneys, © Jaume Meneses, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED

Nature as Divine Inspiration for Gaudí

Among the differential components of Gaudí’s architecture is his inspiration in nature. Although we can also find it in projects by Domènech i Montaner, for example, in Gaudí’s work it will be present from the beginning and will gain relevance as he reaches his artistic maturity. It will lead him to experiment with forms as unique as suggestive, with reminiscences ranging from mountains to octopuses, and including algae, dragons or bones. Gaudí could also be considered then a precursor of what is currently called biomimetic architecture. One of the motivations for choosing this theme, in addition to his love for encyclopedias and biology treatises, was his manifest faith. What better model for a devout believer to follow than the work of God himself?

Structure According to Gaudí

Another principle that separates Gaudí from his contemporaries is his structural experimentation and innovation. The most emblematic example of this facet of the architect is the famous funicular model of the church for the Colònia Güell, made with ropes and weights, and consisting of a succession of parabolic arches. In fact, parabolic arches are quite rare in the history of architecture and can be considered a hallmark of Gaudí’s identity. But it is not the only example: the structural system of the Casa Milà, in which both the facade and the interior walls lose their load-bearing capacity, allows a flexible distribution and large windows to the outside, applying principles considered avant-garde for the time.

Parabolic arches in the attic of Casa Milà, © Manuel Torres Garcia/Unsplash

Gaudi’s Opera Prima: Casa Vicens and Its Transformation Into a Museum

Casa Vicens allows us to see that Gaudí had a distinct artistic personality from the beginning of his career. Perhaps closer to Arts & Crafts Movement than to Art Nouveau, it already shows the ornamental complexity of later works and details of great originality. Several modifications followed one after the other, the most important being the 1927 extension, in which was built a volume that looked like a replica of the original house, doubling its surface area.

In the 21st century, it was decided to convert it into a museum and the extension was used to articulate a practical but audacious intervention. The operation performed by Martínez Lapeña-Torres Arquitectos, in charge of this remodeling (2018), consists of hollowing out the extension and adding a new staircase, replacing Gaudí’s one, demolished in 1927. The staircase was a functional requirement to make tourist visits viable, but it is also conceived as a sculptural element of great geometric complexity, and thus establishes an asymmetrical but enriching dialogue with the modernista building. It is not a timid or imitative intervention. Martínez Lapeña and Torres are inspired by Gaudí and respect him, but they create something totally new.

Casa Vicens, Antoni Gaudí’s first house, © Pol Viladoms/Casa Vicens

Casa Batlló as a Creative and Chromatic Apogee

Casa Batlló differs from the previous example, as it corresponds to Gaudí’s full maturity stage. It is important to remember that this project was a refurbishing of a pre-existing edifice, that underwent a complete metamorphosis. It went from being a humdrum building to a masterpiece of creativity and one of his most lavish works from the semiotic point of view.

It is also one of the most colorful buildings in Gaudí’s repertoire and this feature serves to point out one of the many aspects in which the architect was ahead of his time. The famous trencadís applied to the façade is a variant of the ceramic cladding used by other modernista architects. The technique, conceived by Gaudí in collaboration with Josep Maria Jujol, consists of creating mosaics from irregular fragments, mostly pieces of broken tiles discarded by manufacturers. From a contemporary perspective, it would be a clear example of recycling, one more aspect in which Gaudí seems to sense the future.

Main façade of Gaudí’s Casa Batlló clad in trencadís, © F. Delventhal/Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.0 DEED

Kengo Kuma’s Homage to Gaudí

The modifications undergone by the Casa Batlló over time have been less dramatic, but the most recent and important deserves to be commented. The Japanese architect Kengo Kuma assumes a surgical intervention but as daring as the one mentioned in the Casa Vicens. His renovation (2021) involves some small areas of the basement and the first floor, among which a new spiral staircase of organic forms and reminiscent of bones is implanted. A reinterpretation of Gaudí’s staircase to access the private area of the Batlló family.

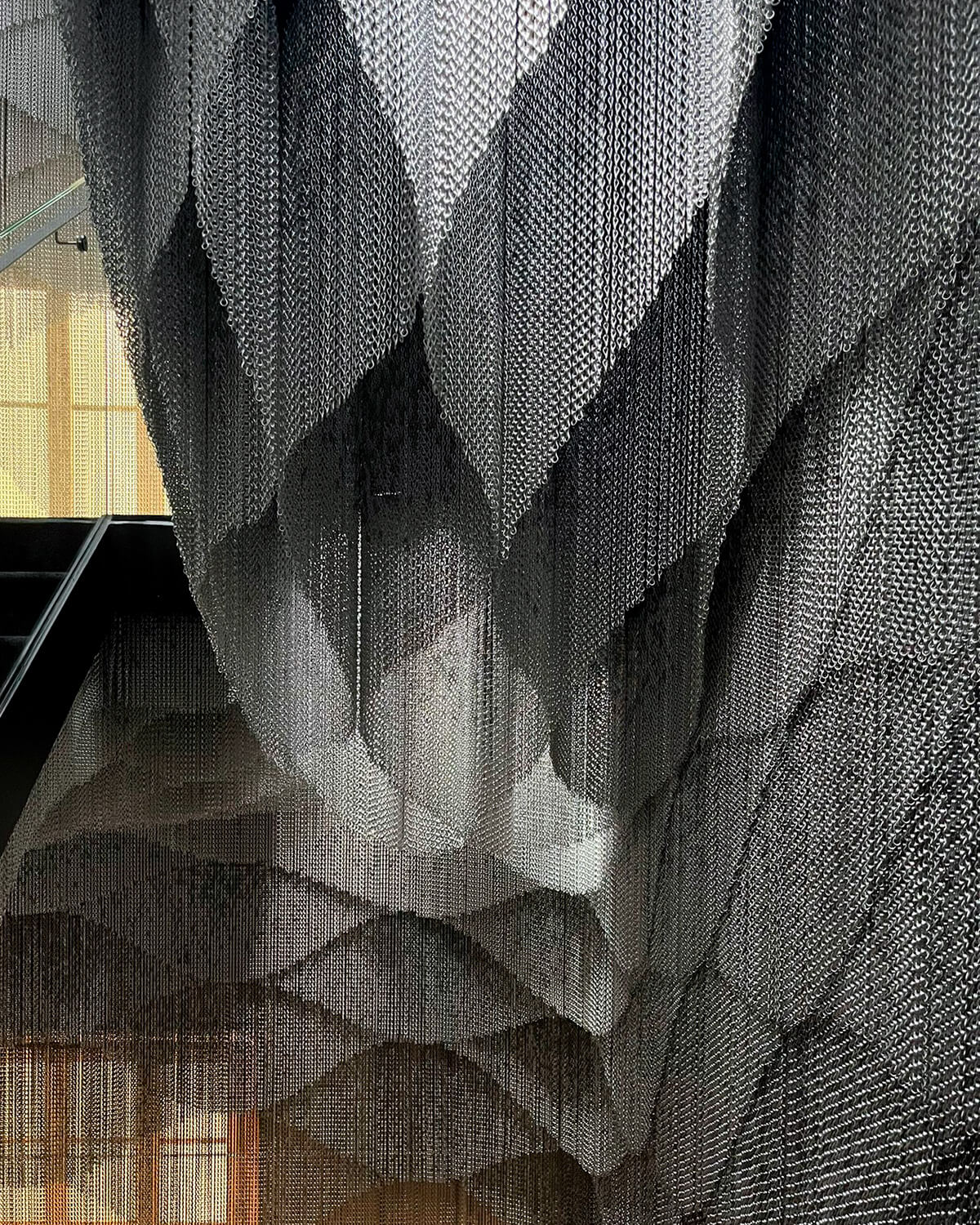

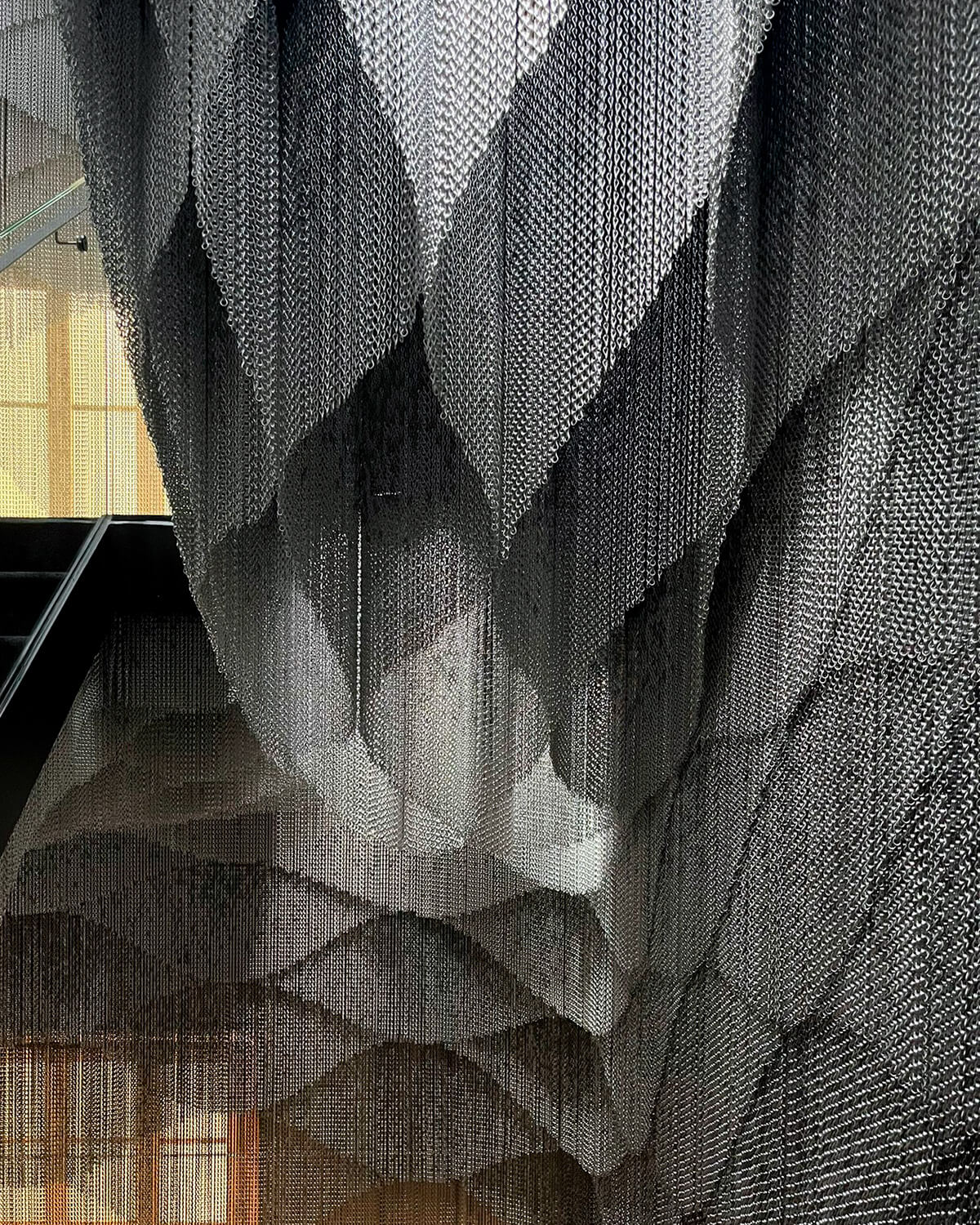

The most important intervention, however, takes place in an evacuation staircase that connects the entire building vertically. This circulation space is incorporated into the touristic itinerary but at the same time is transformed into a sculptural installation. Kuma replaces the wood, usual protagonist of his work, with aluminum chains that are used to create an installation of undulating textures, immersive and highly sensory. The source of inspiration is the funicular model for the Colònia Güell church and its catenary forms, but the result is unmistakably a contemporary work that seems to flirt inadvertently with the modernista building and even with other Gaudí projects.

Kengo Kuma’s sculptural mesh curtain in Casa Batlló, © GA Barcelona

Casa Milà, Forerunner of the Free Floor Plan

The various renovations carried out within the Casa Milà in recent decades are also indicative of Gaudí’s connection with the contemporary. Starting with the dismantled apartments designed in 1955 by Francisco Barba Corsini in the attic of La Pedrera and continuing with the transformation of the main floor into an exhibition hall. The opening of this space through the disappearance of the partitions is one of the most emblematic and perhaps undervalued examples of the real and potential qualities of Gaudí’s architecture. It is a clear demonstration of the free plan system, consolidated only in the 1920s by the advocators of modern architecture, led by Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. In fact, the latter showed his admiration and respect for Gaudí’s work, and for this building in particular, by identifying common principles, which also included the free façade and the roof garden, while pointing out the divergence of the resulting designs.

Antoni Gaudi’s Casa Milà, © Thomas Ledl, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED

Gaudí applied the free plan here in an almost empirical, and certainly unorthodox way: stone columns and metal beams forming a constellation, rather than a grid. The architect’s intention was certainly not to create a large, open, flowing space, but his structural audacity allows just that: the exhibition hall, as well as the so-called Espai Gaudí, located in the attic and implemented in 2006, demonstrate the structural and functional flexibility of the Milà House, prolonging the life of the building beyond its initial purpose.

The dialogue proposed by Toyo Ito between La Pedrera and his Suites Avenue Apartments (2009), located on the opposite sidewalk of the Passeig de Gràcia, is another example of the relevance of Gaudí as a source of inspiration in recent architecture. Ito emulates the undulations of the modernista building in the form of a double façade, a distinctive feature of his repertoire, in which curved metal sheets are projected in front of a glazed plane.

Suites Avenue Apartments by Toyo Ito on Passeig de Gràcia in Barcelona, © Luís Alvoeiro Quaresma/Unsplash

The Sagrada Familia, an Unfinished Symphony

Finally, it is inevitable to talk about the Sagrada Familia. A controversial project and very different from the others, it also symbolizes the connection between Gaudí and the contemporary. Gaudí took over an ongoing and rather uninteresting project to turn it into another architectural singularity. So unique, that his death would bring decades of apparent paralysis in the works. Eventually, private initiatives would launch into the impossible task of finishing the church but would also run into all kinds of obstacles. Starting with the few schematic plans and partial models left by the architect, whose originals had been lost and were recovered through rather debated procedures.

The first difficult decision was made at this point: to attempt to recreate Gaudí’s work without a complete and clearly defined referent. This could be justified in part by considering that the plans for other projects by the architect differ significantly from the finished buildings. But this just demonstrates the difficulty of the enterprise. Gaudí’s works were never blueprints translated directly into reality. They were evolutionary processes in which the elements developed and changed until they took their final form. A process impossible to emulate without the architect from Reus.

Like it or not, perhaps the approach of the sculptor Josep Maria Subirachs, who tried to “appropriate” the premises of the Sagrada Familia and build complementary elements but clearly differentiated from those by Gaudí, was more successful. This is what we see in the Passion façade, where the towers are very similar to the originals, but the angular sculptural elements acquire a very distinctive character.

The Sagrada Familia, Antoni Gaudí’s unfinished masterpiece, © Canaan, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED

In more recent decades, the church has continued to grow at an accelerated pace, clearly exceeding the scope of what can be attributed to Gaudí as an architect. The execution of the nave and the additional towers constitute a challenge whose constructive solution deserves recognition, but it is difficult to assess its appropriateness uncritically. There is something of an impossible task in continuing Gaudí’s project without his participation, and perhaps it would be more consistent to assume this building as a medieval church, in which different authors intervene, sometimes leaving their personal stamp. The impressive forest of columns in the nave, the most striking element of this recent stage, is obviously inspired by Gaudí’s principles but should be considered a contemporary work rather than a “simple continuation” of an unfinished project.

Columns in the interior of the Sagrada Familia, © Yabba You, licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0 DEED

Antoni Gaudí, a Continuous Source of Inspiration

Through these examples, which are not the only ones, we wanted to demonstrate the contemporary relevance of Antoni Gaudí. A fascinating and even contradictory architect, whose legacy is not limited to the works that he managed to achieve. He is an unavoidable reference to get to know the architecture of Barcelona, but also to understand the history of Western architecture, and even aspects of current architecture.

It might be unnecessary to recommend that you visit one or more of Gaudí’s works on your next trip to Barcelona, but we do suggest that you also observe closely the contemporary renovations or extensions that are inspired by his work and sometimes complement it.

Text: Pedro Capriata

Sagrada Familia pinnacle, © Mireia Garcia Bermejo, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ES DEED

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bassegoda, J. (2002). Gaudí o Espacio, luz y equilibrio. Criterio Libros.

Centre Obert d’Arquitectura (s.f.). ArquitecturaCatalana.Cat. https://www.arquitecturacatalana.cat/en

Frampton, K. (1992). Modern Architecture. A Critical History. Thames and Hudson.

Gaudí, A. (1982). Manuscritos, artículos, conversaciones y dibujos. Colegio oficial de aparejadores y arquitectos técnicos de Madrid.

Giralt-Miracle, D. (2002). Gaudí: La recerca de la forma: Espai, geometria, forma i construcció. Ajuntament de Barcelona.

Kengo Kuma and Associates (s.f.). https://kkaa.co.jp/en/

Lahuerta, J. J. (1993). Antoni Gaudí 1852-1926: arquitectura, ideología y política. Electa.

Lahuerta, J. J. (2002). Casa Batlló. Gaudí. Barcelona. Triangle Postals.

Lahuerta, J. J. (2010). Humaredas. Arquitectura, ornamentación, medios impresos. Lampreave.

Lahuerta, J. J. (2016). Antoni Gaudí. Fuego y cenizas. Tenov.

Pevsner, N. (2011). Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius. Palazzo.

Ramírez, J. A. (1992). Gaudí. Grupo Anaya.

Ramírez, J. A. (1998). La metáfora de la colmena: de Gaudí a Le Corbusier. Ediciones Siruela.

Selz, P. (Ed.) (1972). Art Nouveau: Art and Design at the Turn of the Century. Museum of Modern Art.

Solà-Morales, I. de (1983). Gaudí. Ediciones la Polígrafa.

Solà-Morales, I. de (1992). Arquitectura Fin de Siglo en Barcelona. Gustavo Gili.

Tarragó, S. (Ed.) (1991). Antoni Gaudí. Ediciones del Serbal.

Antoni Gaudí and Contemporary Architecture

The Modernist Genius Transcends Time and Continues to Inspire Today’s Architects

Casa Vicens restoration with sculptural staircase by Martínez Lapeña – Torres Arquitectos, © Pol Viladoms/Casa Vicens

An Approach to the Timeless Figure of Gaudí

Antoni Gaudí’s architecture has fascinated generations of architects and amateurs who have always tried to interpret it, often approaching it as if it were a jumble of enigmas. The symbolic complexity of his work is evident, which has encouraged such approaches. But Gaudí’s work is much more than forms and symbols, and here we will first try to give some basic guidelines that will help to have a global and contextualized vision of his legacy, but above all to understand the validity of his ideas and his work, which were ahead of their time, but which also continue to inspire architects and artists in the creation of contemporary works.

Gaudí and Modernisme

The first step is to understand the social and cultural context in which Gaudí’s work arises. Barcelona underwent a drastic transformation in the last decades of the 19th century, thanks in large part to the industrial revolution, which resulted in an economic boom, a cultural renaissance, but also in social conflicts.

In this context, Modernista architecture appeared as an expression of a new industrial bourgeoisie. A complex, fascinating and even contradictory movement that developed in parallel with international Art Nouveau and absorbed diverse theoretical and stylistic influences, among which Gothic and Moorish architecture (including Islamic and Mudejar references) stand out. From this accumulation of components, a unique architecture emerges, which despite its eclectic tendency, can reach a surprising level of harmony. Moreover, it tries to project itself into the future, incorporating industrial materials and techniques without renouncing exuberant ornamentation. Although Gaudí’s work will be unique in many ways, it is from this perspective essentially Modernista.

Rooftop terrace of Casa Milà featuring sculptural chimneys, © Jaume Meneses, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED

Nature as Divine Inspiration for Gaudí

Among the differential components of Gaudí’s architecture is his inspiration in nature. Although we can also find it in projects by Domènech i Montaner, for example, in Gaudí’s work it will be present from the beginning and will gain relevance as he reaches his artistic maturity. It will lead him to experiment with forms as unique as suggestive, with reminiscences ranging from mountains to octopuses, and including algae, dragons or bones. Gaudí could also be considered then a precursor of what is currently called biomimetic architecture. One of the motivations for choosing this theme, in addition to his love for encyclopedias and biology treatises, was his manifest faith. What better model for a devout believer to follow than the work of God himself?

Structure According to Gaudí

Another principle that separates Gaudí from his contemporaries is his structural experimentation and innovation. The most emblematic example of this facet of the architect is the famous funicular model of the church for the Colònia Güell, made with ropes and weights, and consisting of a succession of parabolic arches. In fact, parabolic arches are quite rare in the history of architecture and can be considered a hallmark of Gaudí’s identity. But it is not the only example: the structural system of the Casa Milà, in which both the facade and the interior walls lose their load-bearing capacity, allows a flexible distribution and large windows to the outside, applying principles considered avant-garde for the time.

Parabolic arches in the attic of Casa Milà, © Manuel Torres Garcia/Unsplash

Gaudi’s Opera Prima: Casa Vicens and Its Transformation Into a Museum

Casa Vicens allows us to see that Gaudí had a distinct artistic personality from the beginning of his career. Perhaps closer to Arts & Crafts Movement than to Art Nouveau, it already shows the ornamental complexity of later works and details of great originality. Several modifications followed one after the other, the most important being the 1927 extension, in which was built a volume that looked like a replica of the original house, doubling its surface area.

In the 21st century, it was decided to convert it into a museum and the extension was used to articulate a practical but audacious intervention. The operation performed by Martínez Lapeña-Torres Arquitectos, in charge of this remodeling (2018), consists of hollowing out the extension and adding a new staircase, replacing Gaudí’s one, demolished in 1927. The staircase was a functional requirement to make tourist visits viable, but it is also conceived as a sculptural element of great geometric complexity, and thus establishes an asymmetrical but enriching dialogue with the modernista building. It is not a timid or imitative intervention. Martínez Lapeña and Torres are inspired by Gaudí and respect him, but they create something totally new.

Casa Vicens, Antoni Gaudí’s first house, © Pol Viladoms/Casa Vicens

Casa Batlló as a Creative and Chromatic Apogee

Casa Batlló differs from the previous example, as it corresponds to Gaudí’s full maturity stage. It is important to remember that this project was a refurbishing of a pre-existing edifice, that underwent a complete metamorphosis. It went from being a humdrum building to a masterpiece of creativity and one of his most lavish works from the semiotic point of view.

It is also one of the most colorful buildings in Gaudí’s repertoire and this feature serves to point out one of the many aspects in which the architect was ahead of his time. The famous trencadís applied to the façade is a variant of the ceramic cladding used by other modernista architects. The technique, conceived by Gaudí in collaboration with Josep Maria Jujol, consists of creating mosaics from irregular fragments, mostly pieces of broken tiles discarded by manufacturers. From a contemporary perspective, it would be a clear example of recycling, one more aspect in which Gaudí seems to sense the future.

Main façade of Gaudí’s Casa Batlló clad in trencadís, © F. Delventhal/Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.0 DEED

Kengo Kuma’s Homage to Gaudí

The modifications undergone by the Casa Batlló over time have been less dramatic, but the most recent and important deserves to be commented. The Japanese architect Kengo Kuma assumes a surgical intervention but as daring as the one mentioned in the Casa Vicens. His renovation (2021) involves some small areas of the basement and the first floor, among which a new spiral staircase of organic forms and reminiscent of bones is implanted. A reinterpretation of Gaudí’s staircase to access the private area of the Batlló family.

The most important intervention, however, takes place in an evacuation staircase that connects the entire building vertically. This circulation space is incorporated into the touristic itinerary but at the same time is transformed into a sculptural installation. Kuma replaces the wood, usual protagonist of his work, with aluminum chains that are used to create an installation of undulating textures, immersive and highly sensory. The source of inspiration is the funicular model for the Colònia Güell church and its catenary forms, but the result is unmistakably a contemporary work that seems to flirt inadvertently with the modernista building and even with other Gaudí projects.

Kengo Kuma’s sculptural mesh curtain in Casa Batlló, © GA Barcelona

Casa Milà, Forerunner of the Free Floor Plan

The various renovations carried out within the Casa Milà in recent decades are also indicative of Gaudí’s connection with the contemporary. Starting with the dismantled apartments designed in 1955 by Francisco Barba Corsini in the attic of La Pedrera and continuing with the transformation of the main floor into an exhibition hall. The opening of this space through the disappearance of the partitions is one of the most emblematic and perhaps undervalued examples of the real and potential qualities of Gaudí’s architecture. It is a clear demonstration of the free plan system, consolidated only in the 1920s by the advocators of modern architecture, led by Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. In fact, the latter showed his admiration and respect for Gaudí’s work, and for this building in particular, by identifying common principles, which also included the free façade and the roof garden, while pointing out the divergence of the resulting designs.

Antoni Gaudi’s Casa Milà, © Thomas Ledl, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED

Gaudí applied the free plan here in an almost empirical, and certainly unorthodox way: stone columns and metal beams forming a constellation, rather than a grid. The architect’s intention was certainly not to create a large, open, flowing space, but his structural audacity allows just that: the exhibition hall, as well as the so-called Espai Gaudí, located in the attic and implemented in 2006, demonstrate the structural and functional flexibility of the Milà House, prolonging the life of the building beyond its initial purpose.

The dialogue proposed by Toyo Ito between La Pedrera and his Suites Avenue Apartments (2009), located on the opposite sidewalk of the Passeig de Gràcia, is another example of the relevance of Gaudí as a source of inspiration in recent architecture. Ito emulates the undulations of the modernista building in the form of a double façade, a distinctive feature of his repertoire, in which curved metal sheets are projected in front of a glazed plane.

Suites Avenue Apartments by Toyo Ito on Passeig de Gràcia in Barcelona, © Luís Alvoeiro Quaresma/Unsplash

The Sagrada Familia, an Unfinished Symphony

Finally, it is inevitable to talk about the Sagrada Familia. A controversial project and very different from the others, it also symbolizes the connection between Gaudí and the contemporary. Gaudí took over an ongoing and rather uninteresting project to turn it into another architectural singularity. So unique, that his death would bring decades of apparent paralysis in the works. Eventually, private initiatives would launch into the impossible task of finishing the church but would also run into all kinds of obstacles. Starting with the few schematic plans and partial models left by the architect, whose originals had been lost and were recovered through rather debated procedures.

The first difficult decision was made at this point: to attempt to recreate Gaudí’s work without a complete and clearly defined referent. This could be justified in part by considering that the plans for other projects by the architect differ significantly from the finished buildings. But this just demonstrates the difficulty of the enterprise. Gaudí’s works were never blueprints translated directly into reality. They were evolutionary processes in which the elements developed and changed until they took their final form. A process impossible to emulate without the architect from Reus.

Like it or not, perhaps the approach of the sculptor Josep Maria Subirachs, who tried to “appropriate” the premises of the Sagrada Familia and build complementary elements but clearly differentiated from those by Gaudí, was more successful. This is what we see in the Passion façade, where the towers are very similar to the originals, but the angular sculptural elements acquire a very distinctive character.

The Sagrada Familia, Antoni Gaudí’s unfinished masterpiece, © Canaan, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED

In more recent decades, the church has continued to grow at an accelerated pace, clearly exceeding the scope of what can be attributed to Gaudí as an architect. The execution of the nave and the additional towers constitute a challenge whose constructive solution deserves recognition, but it is difficult to assess its appropriateness uncritically. There is something of an impossible task in continuing Gaudí’s project without his participation, and perhaps it would be more consistent to assume this building as a medieval church, in which different authors intervene, sometimes leaving their personal stamp. The impressive forest of columns in the nave, the most striking element of this recent stage, is obviously inspired by Gaudí’s principles but should be considered a contemporary work rather than a “simple continuation” of an unfinished project.

Columns in the interior of the Sagrada Familia, © Yabba You, licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0 DEED

Antoni Gaudí, a Continuous Source of Inspiration

Through these examples, which are not the only ones, we wanted to demonstrate the contemporary relevance of Antoni Gaudí. A fascinating and even contradictory architect, whose legacy is not limited to the works that he managed to achieve. He is an unavoidable reference to get to know the architecture of Barcelona, but also to understand the history of Western architecture, and even aspects of current architecture.

It might be unnecessary to recommend that you visit one or more of Gaudí’s works on your next trip to Barcelona, but we do suggest that you also observe closely the contemporary renovations or extensions that are inspired by his work and sometimes complement it.

Text: Pedro Capriata

Sagrada Familia pinnacle, © Mireia Garcia Bermejo, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ES DEED

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bassegoda, J. (2002). Gaudí o Espacio, luz y equilibrio. Criterio Libros.

Centre Obert d’Arquitectura (s.f.). ArquitecturaCatalana.Cat. https://www.arquitecturacatalana.cat/en

Frampton, K. (1992). Modern Architecture. A Critical History. Thames and Hudson.

Gaudí, A. (1982). Manuscritos, artículos, conversaciones y dibujos. Colegio oficial de aparejadores y arquitectos técnicos de Madrid.

Giralt-Miracle, D. (2002). Gaudí: La recerca de la forma: Espai, geometria, forma i construcció. Ajuntament de Barcelona.

Kengo Kuma and Associates (s.f.). https://kkaa.co.jp/en/

Lahuerta, J. J. (1993). Antoni Gaudí 1852-1926: arquitectura, ideología y política. Electa.

Lahuerta, J. J. (2002). Casa Batlló. Gaudí. Barcelona. Triangle Postals.

Lahuerta, J. J. (2010). Humaredas. Arquitectura, ornamentación, medios impresos. Lampreave.

Lahuerta, J. J. (2016). Antoni Gaudí. Fuego y cenizas. Tenov.

Pevsner, N. (2011). Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius. Palazzo.

Ramírez, J. A. (1992). Gaudí. Grupo Anaya.

Ramírez, J. A. (1998). La metáfora de la colmena: de Gaudí a Le Corbusier. Ediciones Siruela.

Selz, P. (Ed.) (1972). Art Nouveau: Art and Design at the Turn of the Century. Museum of Modern Art.

Solà-Morales, I. de (1983). Gaudí. Ediciones la Polígrafa.

Solà-Morales, I. de (1992). Arquitectura Fin de Siglo en Barcelona. Gustavo Gili.

Tarragó, S. (Ed.) (1991). Antoni Gaudí. Ediciones del Serbal.